A

delegation of international architects recently toured Liguria’s stoneworking

areas - including a number of quarry sites - as part of a trip arranged by the

Italian Trade Commission.

Although the Liguria region of Italy is not as storied as the historic stoneworking centers of Verona and Carrara, the area is home to a wide variety of stone architecture as well as a number of innovative stone producers. This past November, the Italian Trade Commission showcased Liguria’s stone industry to a delegation of international architects, including professionals from the U.S., the Netherlands, France, Brazil and the U.K.

The program included tours of the slate district of Lavagna, where material is quarried for architectural applications as well as billiard tables and blackboards. (In fact, the word “blackboard” in Italian is Lavagna, while the word for slate is Ardesia.) Architects also had the opportunity to visit two different quarries for Rosso Levanto and Verde Levanto marble, along with an ultra-modern tile-processing plant. They also studied the historic stone architecture of the Liguria region.

The

architects began with a meeting at the Genoa Urban Lab, an initiative of the

city that involves design and urban planning professionals from Italy and

abroad. The goal of the Urban Lab is to improve the city’s overall

infrastructure.

The goal of the Urban Lab is to improve the city’s overall infrastructure with improvements that respect Genoa’s different environments of the neighboring sea and mountains. This includes urban renewal of spaces that are inland from the port as well as improving Genoa’s connection to the rest of Italy and Europe through improved railways.

It is expected that as Genoa’s revitalization progresses, natural stone will play a role in the areas of new construction, such as mixed-use high-rise projects. Stone restoration will also be critical as the city’s palazzos - many of which are in disrepair - are upgraded for modern-day functions.

Also

in Genoa, an introduction to Liguria’s stone resources could be found at the

“BI” product exhibition - held in the city’s famed Palazzo Ducale. This event,

which was organized by noted architect Francesco Lucchese, was a collaboration

of stone suppliers and designers to create new uses for the region’s slate and

marble products.

The resulting exhibition included materials such as Rosso Levanto and White Carrara marble - as well as slate - being utilized for objects such as modern lamps, bookends, serving trays and other decorative items. One of the most intricate projects was an ornate lamp designed by Des Setsu and Shinobu Ito and fabricated by Technotiles S.p.A., a large-scale stone producer in the Liguria region. The stone pieces for the lamp, which was made from White Carrara marble, was formed using a waterjet. Moreover, a combination of Plexiglas and marble provides light diffusion, and Technotiles had to devise an adhesive formula that would work effectively with both materials.

Following the tour of the exhibition, stone industry leaders from the region gave a joint press conference with members of the Italian Trade Commission, and the architects also had a chance to meet with the various suppliers who were involved in the project.

The following articles offer a detailed look at the program.

Showcasing

the history of Liguria’s stone materials, architects were given a tour of many

palazzos and churches within Genoa as well as outside the city.

The palazzos and churches of Liguria

Centered in Genoa and radiating out to the countryside, the Liguria region features a notable range of classic architecture, and much of it includes natural stone as a signature element. As part of their education on Liguria’s stone materials, the architects were given a tour of many palazzos and churches within Genoa as well as outside the city.

The

tour opened up at the Palazzo Ducale (Palace of the Doges) in Genoa, which

features a range of materials from the Liguria region, including Rosso Levano

and Rosso Verde marble. Stone materials were also brought in from the Tuscany region as well as Siena.

The tour opened up at the Palazzo Ducale (Palace of the Doges) in Genoa, the first parts of which were built between 1251 and 1275.

The building is among the first examples of neoclassical work in Italy, and it features a range of materials from the Liguria region, including Rosso Levano and Rosso Verde marble. Stone materials were also brought in from the Tuscany region as well as Siena. Meanwhile, the columns at the building’s main entrance and courtyard are comprised of White Carrara marble. Much of the stone used for the building was transported to Genoa via the sea.

The

columns at Palazzo Ducale’s main entrance are comprised of White Carrara

marble.

The building is now a government-owned facility and the site of political conferences. It also hosts a range of cultural initiatives for the people of Genoa.

Originally

founded in the fifth or sixth century AD, the building that now houses the San

Lorenzo Cathedral in Genoa was started in 1307, and it features alternating

horizontal bands of dark and light stonework - an element that is common among

many notable structures in the Liguria region.

Originally founded in the fifth or sixth century AD, the building that now houses the San Lorenzo Cathedral in Genoa was started in 1307 and continued in various forms until the end of the 17th century. It was designed in a French Gothic style, and it features alternating horizontal bands of dark and light stonework - an element that is common among many notable structures in the Liguria region.

Local

stone was used for much of the design of the San Lorenzo Cathedral, and some of

the most intricate stonework can be found at the entryways. Ornate elements

such as carved columns and detailing are combined with inlaid stone mosaics

across much of the entrance.

Located

in Cognoro - part of the Lavagna slate district about 40 minutes outside of

Genoa - the Basilica dei Fieschi dates to the middle of the 13th century. While

the exterior architecture is similar to that of many churches and cathedrals in

Genoa, it features

slate as a predominant building element - inside and out. The stone was taken

from nearby Monte San Giacomo and the Fontanabuona Valley.

About 40 minutes outside of the city of Genoa lies the Lavagna slate district, and while much of the region is rural in nature, classic styles of architecture can still be found - particularly among its churches. One example of this is the Basilica di San Salvatore dei Fieschi - more commonly known simply as the Basilica dei Fieschi - located in the city of Cognorno.

Slate

flooring was used throughout the interior of the Basilica dei Fieschi.

The exterior also utilizes White Carrara marble, which was used for cladding as well as some of the columns.

The Basilica dei Fieschi remains a centerpiece of the region’s culture, and its courtyard is the site of an annual neo-medieval event known as the “Torta dei Fieschi,” which takes place every August 14. The celebration is a recreation of the festivities that surrounded the wedding of Count Opizo Fieschi, older brother of Sinibaldo Fieschi, who would become Pope Innocent IV and initiate the building of the basilica in 1245.

Ardesia

Biggio srl has been processing slate since 1925, and its finished products

include building materials as well as slate for billiard tables.

Processing slate since 1925

The Lavagna slate region features a range of producers - including long-tenured craftsmen as well as plants equipped with the most modern technology. Among the first exporters of Italian slate on a broad scale, Ardesia Biggio srl has been in operation since 1925.

Ardesia

Biggio’s quarries are located underground, typical of the Lavagna slate region,

and one site is located adjacent to its main processing plant.

Like most slate producers in the Lavagna region, Ardesia Biggio’s quarries are located underground, and one site is located adjacent to its main processing plant. The coloration of the company’s slate tends towards pure black, with a slight hint of gray, and the goal is to process slate that is as consistent as possible.

Experienced

workers split the blocks into slabs along the natural cleave of the material.

The

coloration of the company’s slate tends towards pure black, with a slight hint

of gray, and the goal is to process slate that is as consistent as possible.

Before shipping, slabs are packaged in plastic and wooden frames as needed. In addition to slab production, Ardesia operates a second factory for slate roofing, paving and architectural elements.

Ardesia

Mangini Angela & Donatella snc processes slate into a range of finished

products, including slabs, paving, cladding, countertops, architectural pieces,

roofing and other elements.

An innovator in slate production

Located in the Fontanabuona Valley, Ardesia Mangini Angela & Donatella snc produces first-quality Italian slate, and it reports that it has been exploiting its own quarries for generations. It processes a broad range of products, including slabs, paving, cladding, countertops, architectural pieces, roofing and other elements. Lately, it has also been developing some new finishes and textures, such as “Black Gold,” which includes gold leaf as part of the finished product; and “Black Crocodile,” which has a uniquely detailed surface that resembles the skin of a crocodile.

During

tile processing, the blocks are first cut into cubes and small, squared blocks

on a Bisso bridge saw.

The

squared blocks are split into tiles by hand by experienced stoneworkers, who

must find the natural seam of the stone by eye before splitting.

The company processes approximately 32,000 square feet of material per month, about half of which is exported.

Lately,

Ardesia Mangini has also been developing some new finishes and textures, such

as “Black Gold,” which includes gold leaf as part of the finished product; and

“Black Crocodile,” which has a uniquely detailed surface that resembles the

skin of a crocodile.

Ardesia

Cueno Angiolino & C. was one of the first companies in the slate sector to

use modern equipment for slate extraction and processing. The company has been

in the marketplace for more than 40 years, and its current factory is more than

85,000 square feet in size.

Working slate with advanced technology

Ardesia Cueno Angiolino & C. made a name for itself in the slate sector for being one of the first companies to use modern equipment for slate extraction and processing. The strategy to be on the cutting edge of technology has stayed with the company over the years, and it utilizes a broad range of advanced machinery from Italy in its operation.The company has been in the marketplace for more than 40 years, and its current factory, which is situated inland from Lavagna is more than 85,000 square feet in size.

Among

the modern machinery in place, an Omag Mill 98 CNC stoneworking center offers

automated processing for elements such as kitchen countertops, inlaid tables,

vanity tops, fireplaces and architectural carving.

Meanwhile, tiles are produced on an automated line from Socomac.

Ardesia

Cuenoa invested in a waterjet for intricate cutting of slate and other

materials, and it has produced inlaid medallions combining a variety of stones.

Automated

edge processing is completed using an Omega 60 edger from Comandulli, which can

process materials ranging from 20 to 60 mm thick.

Additional Photos from Working slate with advanced technology

Slate

from Ardesia Cuenoa has been used for a variety of residential and commercial

applications.

The

company’s slate can be used for both interior and exterior applications.

Ditta

Esmar srl’s quarry for Rosso Levanto marble lies high atop the hills of

Bonassola, near the Ligurian Sea, and there are a number of ancient quarry

sites in the area.

Operating an historic quarry site

Approaching Ditta Esmar srl’s current site for Rosso Levano marble in Bonassola (La Spezia Province), there is evidence of several quarries that were established during the Roman Period. And the company’s owners proudly point out these areas as evidence of the material’s importance over the years.“It is one of the traditional stones of Italy, and it was a material for kings,” explained Catarina Rezzano of Ditta Esmar, who operates the company along with her husband. Vitorio. “It is now a family passion for us.”

A

diamond wire saw from Pellegrini is a key piece of equipment during stone

extraction, and blocks are completely squared.

A diamond wire saw from Pellegrini is a key piece of equipment during stone extraction, and blocks are completely squared. Heavy equipment such as a Caterpillar 215 backhoe is also used to clear waste and maneuver materials. Meanwhile, blocks are lifted from the quarry using a derrick crane.

A

derrick crane is used to lift blocks from deep within the quarry.

The

quarry utilizes a Caterpillar 215 backhoe to clear waste and maneuver

materials.

Levante

Marmi srl’s site for Rosso Levanto marble is yielding blocks with a consistent

red color, and it can continue quarrying 130 feet deeper from its present

position.

Seeking pure Rosso Levanto

At Levante Marmi srl’s site for Rosso Levanto marble in Deiva Marina (La Spezia Province), the company is committed to finding the purest material possible. Its current location in the quarry is yielding blocks with a consistent red color, and it can continue quarrying 130 feet deeper from its present position - giving Levante Marmi confidence that it will be extracting high-quality material well into the future.

In

extracting the material, the chainsaw is first used to make a horizontal cut at

the bottom of the quarry face, and then larger cuts are made using a diamond

wire saw.

Large-scale

pieces of machinery in the quarry include a backhoe for clearing waste

material.

After

the quality of the block is confirmed, all sides are squared with the diamond

wire saw.

Waste stone is used for a variety of applications, including “river-washed” stones for landscape designs. It also maintains a retail operation with small stone handicrafts.

The

tile production plant at Technotiles S.p.A. of Vezzano Ligure (La Spezia

Province) features an optimal level of automation, and it is equipped with

technology that allows an unprecedented level of quality control.

Making a science of stone production

The tile production plant at Technotiles S.p.A. of Vezzano Ligure (La Spezia Province) is immediately striking for its level of automation and efficiency. But upon closer inspection, the facility houses a range of equipment not typically found in a stone production plant, such as an automatic unit to electronically classify finished tiles based on algorithms.

The

marble tile production is marketed under the “Luce di Carrara” brand, and it is

entirely comprised of White Carrara marble varieties, which are quarried near

the factory.

“Stone

tiles take longer to realize their true color than ceramic tiles, due to the

fact that there is so much water used in the production,” explained company

founder Dante Venturini, adding that this was the motivation to invest in a

large-scale drying line that completely dries each tile so its color can be

properly classified directly on the production line.

After

the tiles within various categories are dried, they move along the line to the

“Flawmaster,” an automatic inspection system that classifies tiles according to

their quality, tonality and shade. The Flawmaster works with a wide set of

algorithms to identify all types of mechanical and decoration defects.

The

factory for classifying and packaging tiles is equipped with the latest

generation of technology from Barbieri & Tarozzi, and human intervention is

practically unnecessary during the process.

In addition to striving for perfect tile production, Technotiles has also partnered with prominent architects on a variety of initiatives. The latest of these is a collaboration with Foster + Partners where certain stone materials are grouped with complementary elements of glass, mirrors and other design elements in sample kits to offer inspiration to designers and homeowners. “We aren’t endorsing a particular stone, but rather we want to inspire the end user with different systems and concepts,” Venturini explained. “You start with stone and other materials, and the added value is the design. We seek to do this every year, and our last collaboration was with Francesco Lucchese for backlit onyx.”

Tile

are stacked and packaged automatically, and robotic forklifts are used to

transport pallets of material around the plant.

“It was not easy to develop,” Venturini said. “We had to formulate the proper glue that would work with the stone and with the Plexiglas, and maintain a holding capacity of 5 kilograms per square centimeter. We also determined that we needed the stone to be at least 1 cm thick, or you would lose the depth of the stone.”

The

finished products are on display in a modern showroom adjacent to the factory.

White Carrara marble can be found in a broad range of modern applications.

Additional Photos from Making a science of stone production

The

tiles are packaged in distinctive “Luce di Carrara” boxes, and each is marked

with all the relevant information for the material.

Technotiles

has also partnered with prominent architects on a variety of initiatives. The

latest of these is a collaboration with Foster + Partners where certain stone

materials are grouped with complementary elements of glass, mirrors and other

design elements in sample kits to offer inspiration to designers and

homeowners.

Another

initiative by the company is “Luce Diffusa,” which combines translucent onyx or

marble panels with Plexiglas. The product is then hung on an innovative rail

system that allows the material to be backlit without showing any support

behind the stone.

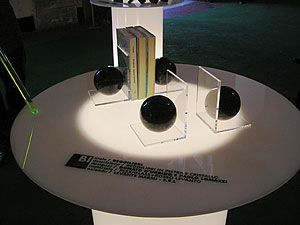

The

focus was to design “everyday” products in stone, such as furnishings and other

household items, such as these bookends that were made using Rosso Levanto

marble and Plexiglas - designed by Donato D’Urbino and Paolo Lomazzi and

processed by Levante Marmi srl.

Additional Photos from Exploring Liguria's stone heritage

Among

the slate products on hand, designer Francesca Macchi conceived decorative

saucers, which were processed by Cueno Angiolino & C.

Combining

slate with White Carrara and Verde Levanto marble, this design by Federica

Fasola was cut on a waterjet by Cueno Angiolino & C.

This

bowl was designed with a floral motive by Luca Scacchetti and is made from

Rosso Levanto marble from Ditta Esmar srl. Different surface finishes on the

bowl’s interior and exterior add to its distinctive look.

One

of the most intricate projects was an ornate lamp designed by Des Setsu and

Shinobu Ito and fabricated by Technotiles S.p.A., a large-scale stone producer

in the Liguria region. The stone pieces for the lamp, which was made from White

Carrara marble, was formed using a waterjet.

Following

the tour of the exhibition, stone industry leaders from the region gave a joint

press conference with members of the Italian Trade Commission, and the architects

also had a chance to meet with the various suppliers who were involved in the

project.