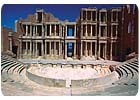

Several different locales within Lybia are showcases of ancient stonework, and they remain attractions in the 21st century. For example, Sabratha's remarkably restored theatre today can seat 1,500 people for performances.

Because I can!†This was the response to my incredulous questioner about why in the world I was going to Libya. But it wasn't just the lure of a once-forbidden land; it was the siren-song of the remains of the Greek, Roman and Byzantine cities that once flourished along the Mediterranean Coast that I really wanted to experience.

Ruins also include the Temple of Demeter, the Greek goddess of fertility, and her daughter, Persophene.

A massive earthquake struck the Mediterranean in 365 AD and virtually destroyed the cities along the African coast, and they never recovered. The Roman Empire was in decline, and vandals attacked the area in the mid-400s AD. In the middle of the 7th century AD, the Arab Muslims arrived and retained control of the area until it was abandoned, left to be covered and preserved for centuries by desert sands, until it was rediscovered by Italian archaeologists in the 1920s.

A detailed marble carving of the classic tragic and comic theatrical masks can be found on the front of the stage of Sabratha's theatre.

Understanding the land

Bounded by Egypt on the east and Tunisia and Algeria to the west, with over 1,000 miles of Mediterranean coastline, Libya is the fourth largest country in Africa. A narrow strip of fertile coastal plain lies along the sea, and the remaining 93% of its land area is desert that reaches far into the Sahara. It is a land of deep and ancient history.The seafaring Phoenicians - based in Tyre, Sidon and Byblos (in modern day Lebanon) - founded a string of safe ports in the natural harbors along the coast of Libya, with Carthage as the governing city. After around 700 BC, they established permanent colonies in the Tripolitania area - Leptis Magna, Oea (today's Tripoli) and Sabratha - to facilitate trade from the Levant to Spain in gold, silver, raw metals, ivory and exotic goods from the interior of Africa. While the Phoenicians were busy in the western parts of the country, the Greeks were establishing Cyrenaica - the cities of Cyrene, Apollonia and Ptolmais in the east.

The Arch of Septimus Severus was built to impress visitors to the city of Leptis Magna.

But the mighty Romans had their sights set on expanding their vast empire. After defeating Carthage and deposing the Berber king, Julius Caesar incorporated Tripolitania as the new province of Africa Nova into the Roman Empire in 46 BC. In the east, Greek rule was fading, and Cyrenaica became part of the Empire in 75 BC. Over the next 400 years, the coastal areas of Libya became prosperous Roman provinces that enjoyed a sophisticated and cosmopolitan culture. The Romans brought their skills as city planners, architects and engineers, and they built theatres, markets, baths, forums, basilicas and amphitheatres. Tripolitania was a major source of olive oil, wheat, barley and wine as well as a transit point for gold and slaves from the interior, while Cyrenaica was prized for its wine, silphium (then a valuable grain but extinct today) and horses.

Using modern-day Tripoli as a base, Sabratha is about 50 miles west and Leptis Magna a little farther east. These Roman cities were magnificent in their day, and today, even to the untrained eye, the ruins take you through the brilliant and sophisticated civilizations that lived, worked and played along the Mediterranean coast.

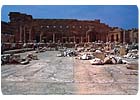

The Severan Forum in Leptis Magna was the center of the city's social and business life. It is a vast open area of 330 x 200 feet that was paved in marble surrounded by two-story colonnaded porticos.

Sabratha

Originally founded by the Phoenicians as a seasonal trading post late in the 5th century BC, Sabratha lay in the shelter of a low barrier reef that protected the shallow-draft boats that plied its waters. By the 2nd century BC, it had become a full-fledged Greek city, protected on its southern edge by the stone quarry from which the city was built. Destroyed by an earthquake around 65 AD, it was rebuilt by the Romans on a grand scale, and it served for nearly 100 years as the judicial center for the province of Africa Nova.

The Arch of Septimus Severus features detailed marble carvings, although they are reproductions. The originals are in the museum in Tripoli.

Gorgon heads, carved in marble, were mounted on the limestone arches surrounding the Severan Forum in Leptis Magna.

Leptis Magna

Leptis Magna, too, had its start as a Phoenician port having been founded at the start of the first millennium BC. But thanks to Septimus Severus, a Libyan who became the Roman Emperor in 193 AD after a brilliant military and political career, the city rose to the peak of its prosperity expanding and building; nothing was too big, too beautiful or too grand for Leptis Magna. Buildings were primarily constructed of local limestone and sandstone, but marbles and granites from all over the Roman Empire were imported to embellish and beautify the baths, the market, the forum, the basilica and the temples.

The Severan Basilica, immediately behind the forum in Leptis Magnam, was originally a judicial basilica and was converted to a Christian church by the Byzantine Emperor Justinian.

The market in Leptis Magna is one of the most unusual buildings in the city and consists of two 60-foot diameter octagonal kiosks set within a rectangle, surrounded on all sides by arcades.

From the baths, the Street of Colonnades leads to the Severan Forum, as ornate and magnificent as any forum in Rome and the center of the city's social and business life. It is a vast open area of 330 x 200 feet that was paved in marble and surrounded by two-story colonnaded porticos. The marble columns rose to arches made of limestone, and on the facades between the arches were Gorgon heads carved in marble, representing the Roman goddess Victory. Wandering through the forum, poking into piles of broken columns and capitals, you wonder what business, gossip and intrigue went on here 2,000 years ago. If only the stones could tell their stories.

Carved marble pilasters adorn the apses of the Severan Basilica in Leptis Magna and show Bacchus with bunches of grapes and acanthus leaves.

One of the most unusual of the Leptis buildings is the market - two 60-foot-diameter octagonal kiosks set within a rectangle surrounded by arcades on all sides. The keystone in the main entrance still shows the carving of the caduceus - the staff of Mercury, god of commerce. Within the kiosks and all around the perimeter, shops were set up selling the bounty of the Leptis merchants and farmers - fruits, vegetables, grains, meats and imported delicacies for the wealthy. There is a reproduction of a stone device for measuring lengths of fabrics, and in the inner arcade, marble bases carved with figures of dolphins may have held counters where the riches of the Mediterranean Sea were sold.

The Sanctuary of Zeus in Cyrenaica was built of limestone and featured banqueting rooms for great numbers of visitors.

Cyrenaica

It is in Cyrenaica that the Greek influence is more strongly seen and felt. Founded in the 6th century BC by colonists from the Greek island of Thera and subsequently ruled by Alexander the Great and the Egyptian Ptolomies, by 75 BC the city had become an important Roman capitol but retained its Greek character and heritage.Set on rolling hills overlooking the blue Mediterranean, the site is spectacular - with the blues of the sea and sky seamlessly merging. From the agora high on a hill, you can see the Sanctuary of Apollo and a rich collection of temples to Artemis, Isis, Mithras and to more obscure and unknown gods and goddesses. Many of these ruins are yet to be excavated, and who knows what wonders still lie there waiting to be discovered? In the hillside are caves that contain the springs of Kyra and Apollo; the water was transported to two fountains in the temple area through a system of conduits and small canals.

The Sanctuary of Zeus lies on the northeastern hill of the city, and excavations have revealed banqueting rooms for great numbers of visitors and rooms where those visitors could leave donations to the temple and its god. The sanctuary is massive and dominates the hill. Built of limestone, the main hall is surrounded by a peristyle of Doric columns, eight columns wide and 17 long. Inscriptions on the architraves record restorations done during the time of the Ptolemys and the reign of the Roman Emperor Augustus.